Sitting in my window seat on a Southwest 737 MAX8, preparing for the short flight from Atlanta to Orlando, I snapped a quick picture of the plane at the gate next to ours. I often do this to get photos to use on our website.

When I got home, I noticed something interesting on the rear of the plane over the aircraft registration.

In smaller writing, above the registration, N8325D, there was another marking. It said 8325 ETOPS.

I’ve heard about ETOPS before and knew it had something to do with flying planes on routes without diversion points. But there’s way more to being an ETOPS-certified plane than that.

Introduction to ETOPS Certification

ETOPS stands for Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards. It’s a rule created by the FAA that permits twin-engine aircraft to fly routes that, at some point, are more than 60 minutes flying time away from the nearest airport suitable for an emergency landing.

Back in the day, twin-engine planes were only allowed to fly on routes within 60 minutes of the nearest airport in case one of the engines failed and the aircraft had to make an emergency landing. That’s because, at the time, that was the longest a plane was deemed to be safe to fly with only one engine.

Only planes with more than two engines could fly the most efficient Trans-Atlantic routes, such as New York to London. This is why those routes were exclusively operated by aircraft like the quad-engine 747 or the tri-engine DC-10, which were not subject to the same rules.

Here’s a great video about the history of ETOPS and how it transformed the global aviation market.

The History and Evolution of ETOPS

Eventually, in 1985, the FAA granted TWA an ETOPS 120 clearance to fly a twin-engine 767 between Boston and Paris. This meant the plane could fly up to 120 minutes from the nearest airport and was the beginning of the ETOPS era. Besides its official meaning, the acronym is also sometimes said to mean “Engines Turn or Passengers Swim.” Having a working relationship with dark humor in the workplace, I totally get and appreciate how and why ETOPS got that alternate name.

Airplane technology has come a long way since the 1980s, and I have no problems flying a twin-engine plane across an ocean. However, I was curious about what made a plane worthy of the ETOPS certification. Was it in some way different than other planes?

In short, yes and no.

What Makes a Plane ETOPS Certified?

As it turns out, a plane with an ETOPS certification isn’t all that different from the same plane without the certification. For instance, why would a Southwest plane in Atlanta be certified to fly more than 60 minutes from the nearest diversion airport?

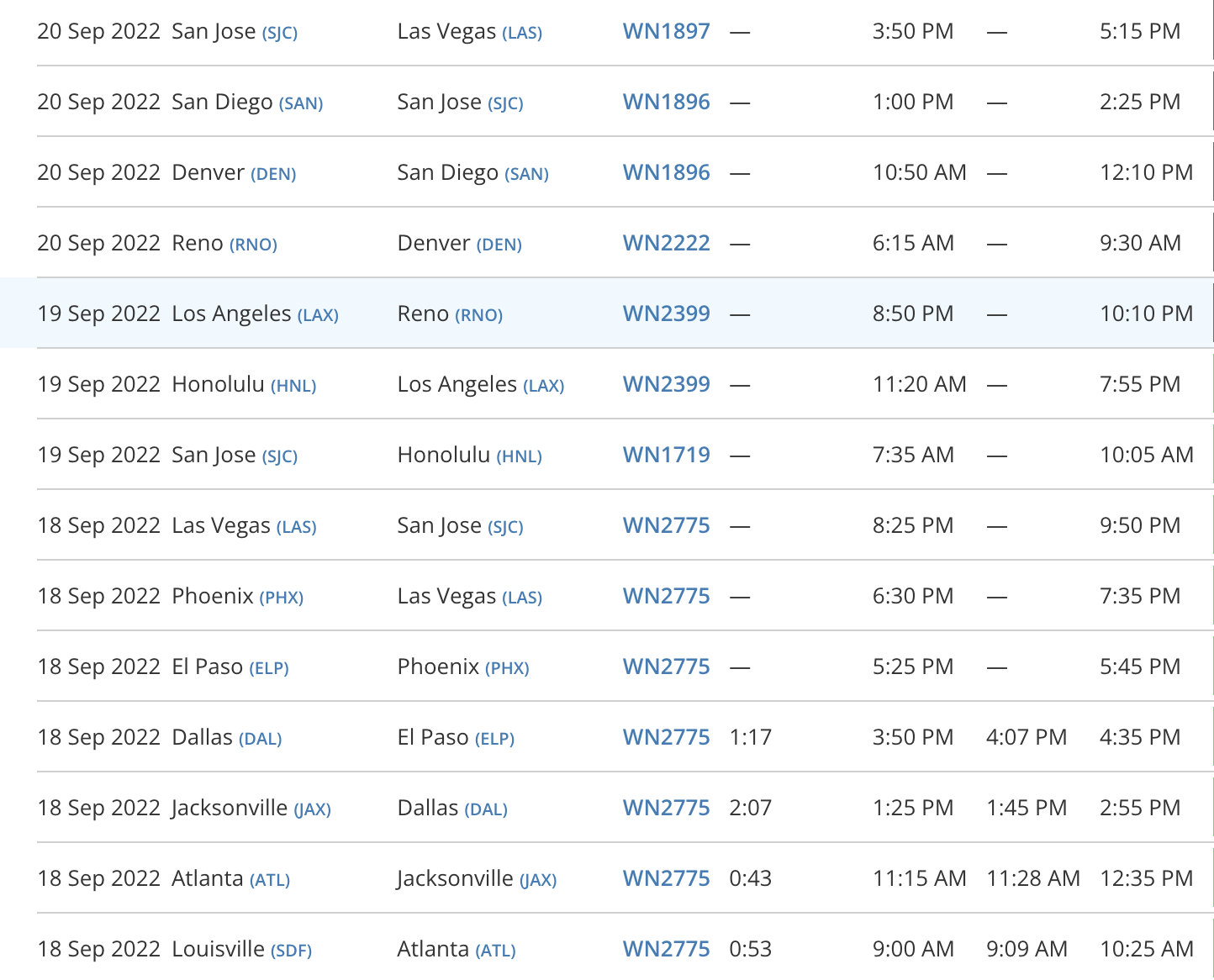

It turns out that besides flying from Atlanta to Jacksonville, Dallas, El Paso, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and San Jose, the same plane makes the trip from San Jose to Honolulu and back to Los Angeles. All flights from the mainland to Hawaii need to be ETOPS certified.

Not all planes are ETOPS-certified. Airlines must apply for each airframe and route, and airplanes flying that route must meet specific requirements.

They are held to a more rigorous maintenance schedule, require additional flight and cabin crew training, have a passenger diversion plan for a route, and have extra redundancy for certain systems, such as electrical, hydraulics, fire suppression, and communications.

Because of the extra costs for maintenance and training, airlines only certify planes that need to be certified. This isn’t to say that a non-ETOPS-certified aircraft can’t fly over the ocean, as this American Airlines flight did in 2015 on a trip to Hawaii. They’re just not approved to make the trip safely.

ETOPS and the Future of Air Travel

Currently, the furthest a plane can fly from a diversion airport is the Airbus A350XWB, which has an ETOPS-370 certification. This means the only place the airplane can not fly is directly over Antarctica.

With twin-engine airplanes able to fly almost anywhere with sufficient ETOPS certification, does this mean the end of quad-engine planes like the A380? For now, probably not. There’s still a market for high-volume planes in certain markets that a twin-engine aircraft can’t provide.

But who knows what new routes we might see with twin-engine planes having an almost unlimited range worldwide?

Want to comment on this post? Great! Read this first to help ensure it gets approved.

Want to sponsor a post, write something for Your Mileage May Vary, or put ads on our site? Click here for more info.

Like this post? Please share it! We have plenty more just like it and would love it if you decided to hang around and sign up to get emailed notifications of when we post.

Whether you’ve read our articles before or this is the first time you’re stopping by, we’re really glad you’re here and hope you come back to visit again!

This post first appeared on Your Mileage May Vary

2 comments

In my new position at BMW in 1985 I was to be working closely with people at the factory in Germany which meant frequent international travel. I’d been there before, flying on a Lufthansa or Swissair 747 or a Lufthansa DC-10. But when I got to JFK that November for my TWA flight I was startled to find that I’d be on a 767. As a former military pilot I am always aware of what I’m flying on, but in this instance no one else seemed to care or so much as bat an eye. Dozens of flights later to Europe, the mid-east and Asia in the last 25 years I’ve flown on nothing but twin engine aircraft.

A friend who’s an aerospace engineer, while noting that she and her peers take aviation safety design very seriously, also admitted they sometimes described ETOPS as Engines Turn or Passengers Swim.