Whenever I’ve boarded a flight and the door to the cockpit is open, I’ve admittedly been nosy and tried to pick up bits of what they’re saying. I never get much.

But over the years I’ve learned about certain words, like “Niner” (pilot-speak for the number nine. It helps differentiate it from the number five [said as “fife”], since the two can sound similar) or sayings like “souls on board.”

That last one always intrigued me. Why do they say “souls on board,” instead of “passengers” or even just “people?” So I decided to find out.

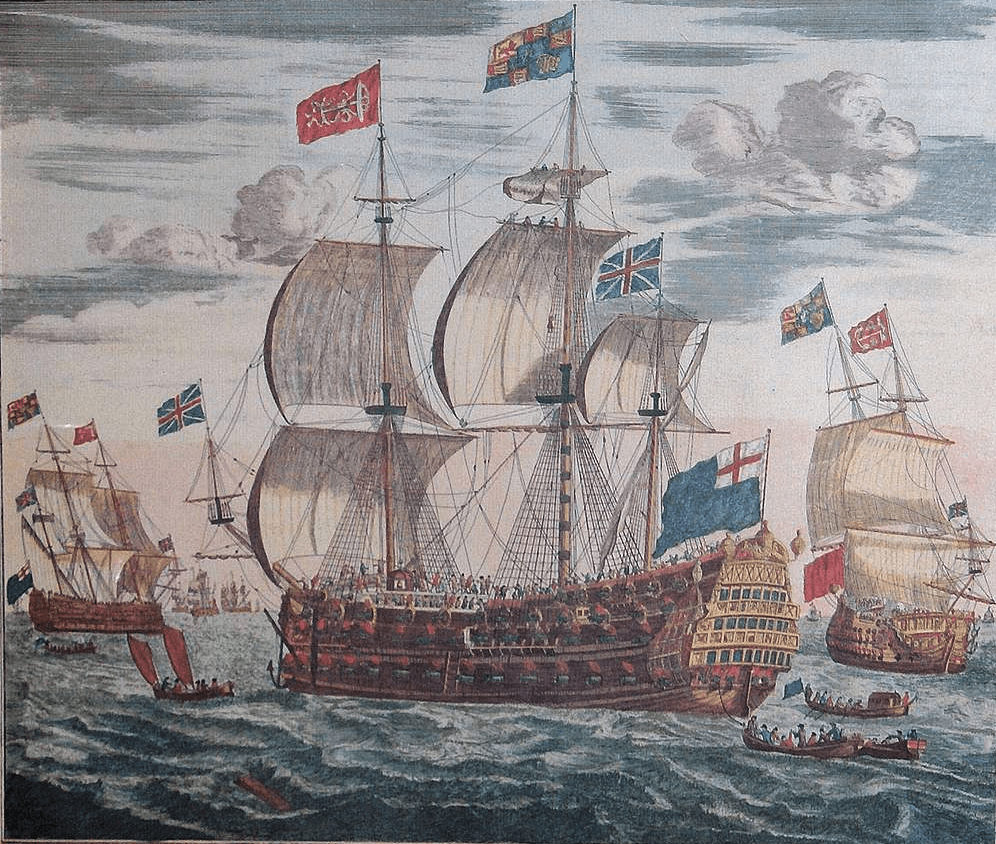

It turns out that the term “souls on board” was originally a nautical reference that goes back to at least the first century. The captain would say there are #### souls on board and that would include everyone on the ship who was alive. It would include, not just the passengers and crew who had been accounted for when the journey began, but also to take into consideration anyone who had passed away during the journey, live births and potentially even stowaways. That way, if the ship were in danger, rescuers, if available, would know how many people to rescue or recover.

The term unofficially continued on in aviation for the same reason. “Souls on board” would include:

The term unofficially continued on in aviation for the same reason. “Souls on board” would include:

- Passengers who have paid for, and have assigned seats

- Lap infants who don’t have assigned seats

- All staff throughout the plane (including “jumpseaters” – off duty personnel)

It’s relatively rare for someone to pass away on a flight (although it happens), but if that were the case, that person wouldn’t be counted as one of the souls on board.

Planes can sometimes carry deceased individuals in the cargo area of the plane. They would also not be included in the count of souls on board.

Surprises, variations & changes

The thing is, the term Souls on Board was never an official term. It’s been handed down over the years, but other terms have always been the official vernacular.

- The International Civil Aviation Organization’s form counts passengers and crew as “Persons on Board”

- The FAA uses the phrase “number aboard”

- FAA Academy uses “Number POB” (short for “persons on board”)

- ATC’s handbook uses “Number of People Aboard”

In 2019, Medium printed a piece, which had been adapted from the FAA’s internal website a few years earlier, that explained why and how Souls on Board, never an official term anyway, was fading away…but also why, in some sectors, it’s stayed around for so long.

Want to comment on this post? Great! Read this first to help ensure it gets approved.

Want to sponsor a post, write something for Your Mileage May Vary, or put ads on our site? Click here for more info.

Like this post? Please share it! We have plenty more just like it and would love it if you decided to hang around and sign up to get emailed notifications of when we post.

Whether you’ve read our articles before or this is the first time you’re stopping by, we’re really glad you’re here and hope you come back to visit again!

This post first appeared on Your Mileage May Vary

3 comments

When a pilot declares an inflight emergency, Air Traffic Control (ATC) wants to know two things beyond what the pilot needs to aviate, navigate and communicate – number of souls on board and amount of fuel onboard in pounds. The fuel quantity is for two reasons: 1 – to know how long the aircraft can stay in the air and 2 – to determine if the plane is within the maximum landing weight to land. That’s why aircraft spray out fuel (dump) while waiting to land to get the weight within max landing weight.

Even though English is the official language of ATC, we still say “niner” because the German word for NO is NEIN.

We don’t say “roger that” or “copy that” because there is no that in that. “That” is from Hollywood movies.

Not quite understanding the weight part. All modern aircraft are certified to land at Maximum Takeoff Weight. Whilst this isn’t done routinely, if the flight crew decide that they need to land NOW, then they will. So left unsure what use that part is to the ground.

I had always believed the fuel load was most useful for ARFF.

It is much easier to understand a word consisting of a couple of different syllables than a single syllable word that can often get cut off by the com equipment. “Niner” is two different syllables. “Nine” can be confused with “five” over a staticky radio.