Hurricane season in the Atlantic runs each year from June 1 through November 30. That means if you decide to visit the outer edges of the southern U.S. quadrant (and sometimes even further out – the number of storms that have affected the U.S. northeast is staggering) any time from late spring to late fall (6 whole months out of the year), you run the risk of being there during hurricane season.

The chances of your visiting somewhere during an actual hurricane are pretty slim. But there’s always the possibility. So here’s some “good to know” info about hurricanes in general, as well as some suggestions of what to do and what can happen if you’re booked to be somewhere during a hurricane.

Why June 1 through November 30?

Those are the dates that historically describe the period in each year when most Atlantic tropical cyclones form (“tropical cyclone” is a generic term used by meteorologists to describe a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and has closed, low-level circulation). Tropical cyclones need warm water (80 degrees and warmer) to form and sustain, which is why they happen during the warmer months of the year. There have been some storms both before and after those arbitrary dates, but not many.

Historically, the chances of hurricanes are greatest between August 15 and October 1.

Types of possible storms

The aforementioned tropical cyclones are classified into one of three categories:

- TROPICAL DEPRESSION: a tropical cyclone that has maximum sustained surface winds (one minute average) of 38mph (33 knots) or less

- TROPICAL STORM: a tropical cyclone that has maximum sustained surface winds ranging from 39-73mph (34 to 63 knots)

- HURRICANE: a tropical cyclone that has maximum sustained surface winds of 74mph or greater (64 knots or greater)

If a storm becomes a hurricane, it gets its own categorization, based on how strong its winds are:

- CATEGORY 1: 74-95 mph / 64-82 kt / 119-153 km/h

Very dangerous winds will produce some damage: Well-constructed frame homes could have damage to roof, shingles, vinyl siding and gutters. Large branches of trees will snap and shallowly rooted trees may be toppled. Extensive damage to power lines and poles likely will result in power outages that could last a few to several days. - CATEGORY 2: 96-110 mph / 83-95 kt / 154-177 km/h

Extremely dangerous winds will cause extensive damage: Well-constructed frame homes could sustain major roof and siding damage. Many shallowly rooted trees will be snapped or uprooted and block numerous roads. Near-total power loss is expected with outages that could last from several days to weeks. - CATEGORY 3: 111-129 mph / 96-112 kt / 178-208 km/h

Devastating damage will occur: Well-built framed homes may incur major damage or removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, blocking numerous roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm passes. - CATEGORY 4: 130-156 mph / 113-136 kt / 209-251 km/h

Catastrophic damage will occur: Well-built framed homes can sustain severe damage with loss of most of the roof structure and/or some exterior walls. Most trees will be snapped or uprooted and power poles downed. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months. - CATEGORY 5: 157 mph or higher / 137 kt or higher / 252 km/h or higher

Catastrophic damage will occur: A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed, with total roof failure and wall collapse. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.

You can click here for an animated example of the type of damage seen at each hurricane level. And click here if you want more heavy-duty info about hurricanes in general. Or watch this if you want to learn more about how they form:

“Warnings” vs.”Watches”

You may hear terms such as “tropical storm warning, hurricane watch” etc. From weather.gov:

- TROPICAL STORM WATCH is issued when Tropical Storm conditions, including winds of 39-73mph, pose a POSSIBLE threat to a specific coastal area within 48 hours.

- TROPICAL STORM WARNING is issued when Tropical Storm conditions, including winds of 39-73mph, are EXPECTED in a specific coastal area within 36 hours or less.

- HURRICANE WATCH is issued when sustained winds of 74mph or higher are POSSIBLE within the specified area of the Watch. Because hurricane preparedness activities become difficult once winds reach tropical storm force, the Watch is issued 48 hours in advance of the onset of tropical storm force winds.

- HURRICANE WARNING is issued when sustained winds of 74mph or higher are EXPECTED somewhere within the specified area of the Warning. Because hurricane preparedness activities become difficult once winds reach tropical storm force, the Warning is issued 36 hours in advance of the onset of tropical storm force winds.

How bad do hurricanes get?

It all depends on the size of the hurricane, where it is, and where you are in relation to it.

When you think of the particularly devastating hurricanes such as what Katrina did to New Orleans, what Andrew did to Homestead or the effects of the Great Storm in Galveston in the year 1900, note that those places are right next to the water. Anywhere that’s closer to water has a higher chance of really bad damage due to a hurricane. The further inland you are, the less damage there will be because the storm will have less access to warm water that allows it to thrive.

That being said, even if you’re significantly inland, you could still see flooding, lose electricity, etc., depending on the characteristics and strength of the storm when it reaches you.

Case in point, in 2004, Hurricane Charley, which made landfall in Punta Gorda, FL (southwest FL) as a Cat 4 storm, was still a Cat 1 storm when it got to us, just 9 miles from WDW. Houses in our neighborhood lost shingles to whole roofs, trees were downed, and although we got services back within 24-72 hours, some people a few miles from us lost electricity for weeks.

Part of our cleanup after Hurricane Charley, Aug. 2004

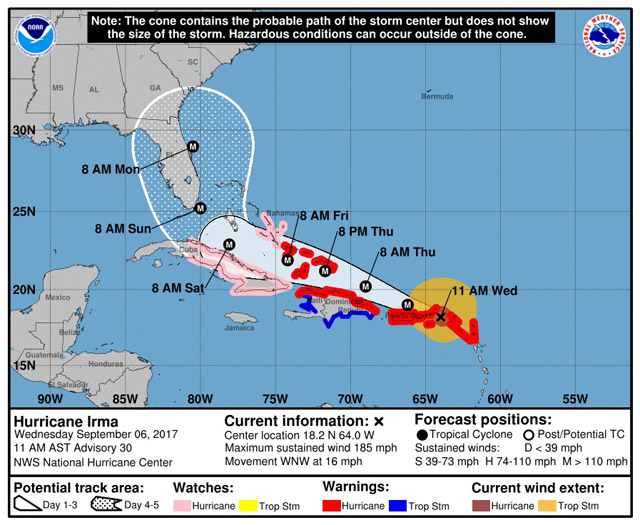

What’s that cone thing they talk about?

From https://fla-keys.com/hurricane-information/:

Although hurricane forecasting has improved each year, it is still an inexact science, especially when the storm is more than three days away.

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) produces two types of tracking maps. The first shows the area of strike possibility from zero to three days out and the second includes four to five days out.

Because hurricane forecasting is not an exact science, NHC forecast tracks of the center line have high error rates, especially forecasts issued more than three days ahead of a potential strike. The average track forecast errors in recent years are used to construct the areas of uncertainty for the first three days (solid white area) and for days 4 and 5 (a white stippled area). For the four- and five-day forecast, the error can be hundreds of miles.

The primary purpose of the four- and five-day track forecast map is that the hurricane center wants people to simply be aware of the storm, think about what actions to take in the event it continues to proceed in their direction, and be ready to follow the instructions provided by emergency management officials and your lodging management.

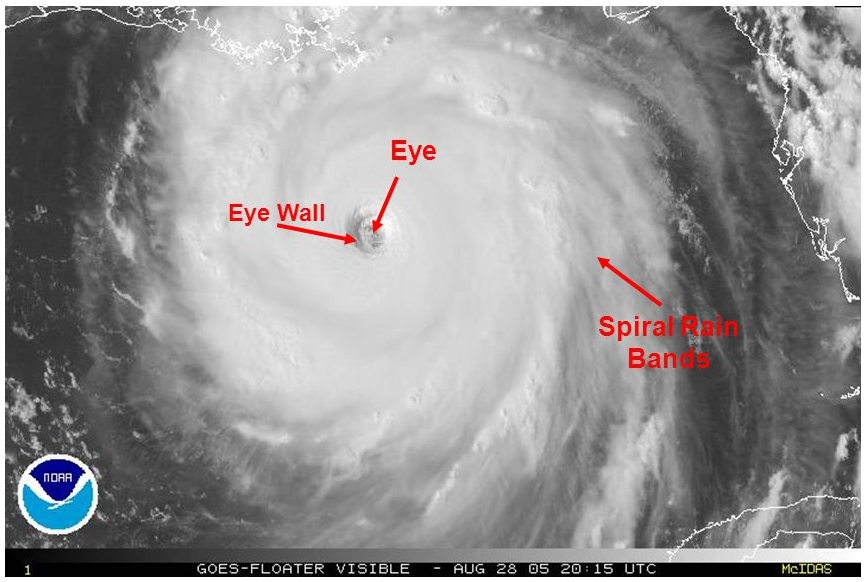

What are the eye, eyewall, and rain bands of the storm?

PC: NOAA

- The hurricane’s core is called the “eye.” It looks like a hole in the middle of the storm. The smaller the eye, the stronger the storm.

- The winds that are closest to the eye, typically averaging about 60 miles from the center of the storm, are the strongest and bring the most potential for damage. Those make up the eyewall.

- Long bands of rain clouds spiral inward to the eyewall, going in a counterclockwise direction (they go clockwise in the southern hemisphere). Those are rainbands and can be hundreds of miles across. Hours before the eye and eyewall are anywhere near you, you may experience rainbands, where it rains, then stops, then rains again, then stops. As the eye approaches, the rainbands will increase in timing and intensity, until it’s just storming all around you, nonstop, until the hurricane passes. Then you’ll get more rainbands again, which will decrease in time and intensity, and then it’s over.

What’s up with naming hurricanes?

Storms are named when they reach tropical storm status and are done to help with communication (especially when there are multiple storms at the same time). Each year there are 21 names “at the ready” to be named for a storm, going in alphabetical order (they don’t name storms for the letters Q, X or Z – just too difficult to keep coming up with names). If there are more than 21 named storms in a year, backup names are available for usage (they used to use the Greek alphabet for backup names, but they retired that process in 2020).

Interesting Facts About Naming Storms:

- From the 1950s through the late 70s, all tropical storm and hurricane names were female. That ended in 1979, when they began using male names, as well.

- Atlantic tropical cyclone names are used in rotation and recycled every six years (ergo, many of the names used in 2023 will be used again in 2029).

- If a storm gains enough notoriety for its death and destruction, its name is “retired” from the list. This page has the list of names, by year, that have been retired.

What if I’m booked to be somewhere and a hurricane is supposed to be coming to the area?

First and foremost, pay close attention to the weather in the area to get a better idea of what could be coming down the pike.

If you were planning on driving, and there’s a good chance that a hurricane could come, seriously, don’t go. Depending on what happens, you could be driving into what soon could become a disaster. Just don’t go. That’s what travel insurance is for (but make sure you buy the insurance before the storm is named; you won’t be able to buy a policy for a trip to a location after a storm headed in “that” direction is named).

If it looks as if a hurricane may impact the area where you’re planning to travel and you were going to fly to get there, chances are good that your flight will be canceled. Airlines are more interested in getting people and planes out of there, much less so than getting people into an area.

What if I’m booked to be on a cruise and a hurricane is supposed to be on its way?

Cruise companies follow the weather very carefully. They can and will change itineraries, cancel sailings, and work hard to keep passengers and crew out of harm’s way.

If you’re scheduled to be on a cruise and you see a hurricane is on its way to where your port is, contact the cruise company. Depending on where and when the cruise ship is supposed to make land, the cruise company may choose to extend the cruise just before yours, letting it sit in the ocean, out of harm’s way. In that case, your cruise may be canceled. Better to know that before you leave home.

Not that if your cruise company cancels your cruise, you will still need to contact any other companies involved in getting you to the cruise (i.e. airlines, hotel and/or car rental in the days before AND AFTER your cruise) to discuss cancellation options.

Unless you purchased a package through your cruise line, your cruise line will not be responsible for any money you paid for airlines, car rentals, hotels, etc. surrounding your cruise. Again, this is why it’s good to have travel insurance.

What if I’m already in an area that may be impacted by a hurricane?

Again, pay close attention to the weather to determine what your next move should be.

Things to do before the storm:

- Get cash (if there’s no electricity, ATMs won’t work, and you won’t be able to make credit or debit card purchases)

- Buy (or bring from home) a small, battery/solar/hand-crank radio, bottled water to last a few days, and a flashlight (and enough batteries, if needed, to get you through several days)

- Have access to a car? Fill the tank with gas and/or top off that electric battery (gas and charging stations don’t work if there’s no power)

- Have a map (an actual, physical map, not one on your phone – you’ll waste potentially precious battery power looking at it), with your evacuation route clearly marked

- Charge all of your electronics so their batteries are full (again, if there’s no power, you won’t be able to recharge, so make sure you are fully charged while you still can)

- Tell your family and friends exactly where you’re going to ride out the storm (including the address – there are lots of Marriotts in some cities) and give brief updates during the storm (if you can), so they know you’re OK.

As the storm approaches:

- If you’re near the coast and it looks as if the area where you are is going to be impacted (via the news, weather, talking to those who live there, etc.), go inland if you can, where damage from wind and storm surge (read: extreme flooding from the ocean/gulf – can range from 4 to 20 feet) might not be as severe. Remember: “Run from water, hide from wind.”

- If a hurricane evacuation is called, follow the instructions you’re given. You may be in a flood zone and could die if you don’t leave when told to. Also, if you’re told to evacuate, choose not to, and then are in a dangerous situation in the middle of the storm, no one is going to be able to help you until the storm calms down.

- If you can’t leave (no car, can’t catch a flight, bus, etc.), find out where the nearest hurricane shelter is, and consider relocating there before the storm arrives (if you have a pet with you, find one that specifically says they accept pets. Many don’t.).

- Talk to the people who work at your hotel – they should have a hurricane plan. Do they recommend staying at the hotel? If so, then do so and listen to their instructions (i.e. they may suggest staying in a spot without windows, such as a ballroom or convention space, instead of your hotel room [big windows on high floors {where winds are stronger} are more apt to break during a hurricane]).

What if I’m on a cruise during a hurricane?

Today’s modern cruise ships are built to withstand storms, avoid them, and even outrun them. As started above, the cruise companies will follow the weather very carefully and make changes accordingly. Your itinerary may change last-minute, as the captain could bring you to locations and/or ports with calmer seas. You may find your eastern Caribbean cruise to the Bahamas, St. Thomas, and St. Maarten is changed to a western Caribbean cruise to Jamaica, Grand Cayman, and Cozumel, or the opposite. You may even be at sea for an extra day or two in order to avoid the storm. The cruise company’s most important goal is to keep its passengers safe.

Special considerations if you’re in a tourist area:

All theme parks and attractions (especially in Central Florida) have hurricane (or at least “weather”) policies related to park closings and keeping vacationers safe. States, counties and coastal areas have info, as well:

- The Florida Keys & Key West

- Fort Lauderdale

- The State of Georgia

- Hilton Head

- Jekyll Island

- Lakewood Camping Ground

- Legoland

- Miami

- Myrtle Beach

- SeaWorld, Discovery Cove, Aquatica, Busch Gardens, Adventure Island: “In the event a named tropical storm or hurricane approaches Orlando, Tampa, or a guest’s hometown, the parks will reschedule or refund any vacation package and/or individual park tickets booked through SeaWorld Vacations, Busch Gardens Vacations, DiscoveryCove.com, SeaWorld.com, Aquatica.com, BuschGardens.com, or the call center. The parks will not apply any cancellation or change fees for this service.”

- Schlitterbahn Galveston – will close due to hurricanes

- Six Flags

- The State of Texas

- Tybee Island

- Universal Orlando

- VisitFlorida

- Walt Disney World

No one wants to be in a hurricane – if you have plans to be somewhere that may get one, don’t go. If you’re already there, evacuate if you can. Or, if not, follow the directions given to you by those who understand hurricane preparedness better than you do.

Feature Photo: Public Domain

Want to comment on this post? Great! Read this first to help ensure it gets approved.

Want to sponsor a post, write something for Your Mileage May Vary or put ads on our site? Click here for more info.

Like this post? Please share it! We have plenty more just like it and would love it if you decided to hang around and sign up to get emailed notifications of when we post.

Whether you’ve read our articles before or this is the first time you’re stopping by, we’re really glad you’re here and hope you come back to visit again!

This post first appeared on Your Mileage May Vary